Syringomas are benign tumors originating from the eccrine sweat ducts, specifically from the intraepidermal portion known as the acrosyringium. These small, firm papules commonly appear in clusters, particularly around the lower eyelids, though they can also be found on the cheeks, scalp, armpits, umbilical region, chest, and genital areas. The term “syringoma” comes from the Greek word syrinx, meaning tube or pipe, reflecting the tubular structure of these tumors.

Classified into four main types according to Friedman and Butler’s system, syringomas may present as localized lesions, generalized multifocal or eruptive forms, inherited familial syringomas, or those associated with Down syndrome. Although syringomas are relatively uncommon, affecting about 1% of the population, they tend to develop sporadically, typically during or after adolescence. They occur more frequently in women than in men, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:2. However, some individuals inherit the condition in an autosomal dominant pattern, often experiencing the appearance of syringomas before puberty, particularly on the face.

Certain genetic and medical conditions have been linked to syringomas, especially those that appear on the eyelids. Individuals with Down syndrome exhibit a notably higher prevalence, with studies estimating an incidence of 18% to 39%. Other associated syndromes include Marfan syndrome, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, and Brooke-Spiegler syndrome. The eruptive variant of syringomas, which appears as crops of hyperpigmented papules, is more commonly observed in individuals of Asian descent, those with darker skin tones, and patients with Nicolau-Balus syndrome. In some cases, hormonal changes, such as those occurring during pregnancy, may contribute to the development of vulvar syringomas. A rare subtype known as clear cell syringoma is characterized by the presence of glycogen deposits and has been associated with diabetes mellitus.

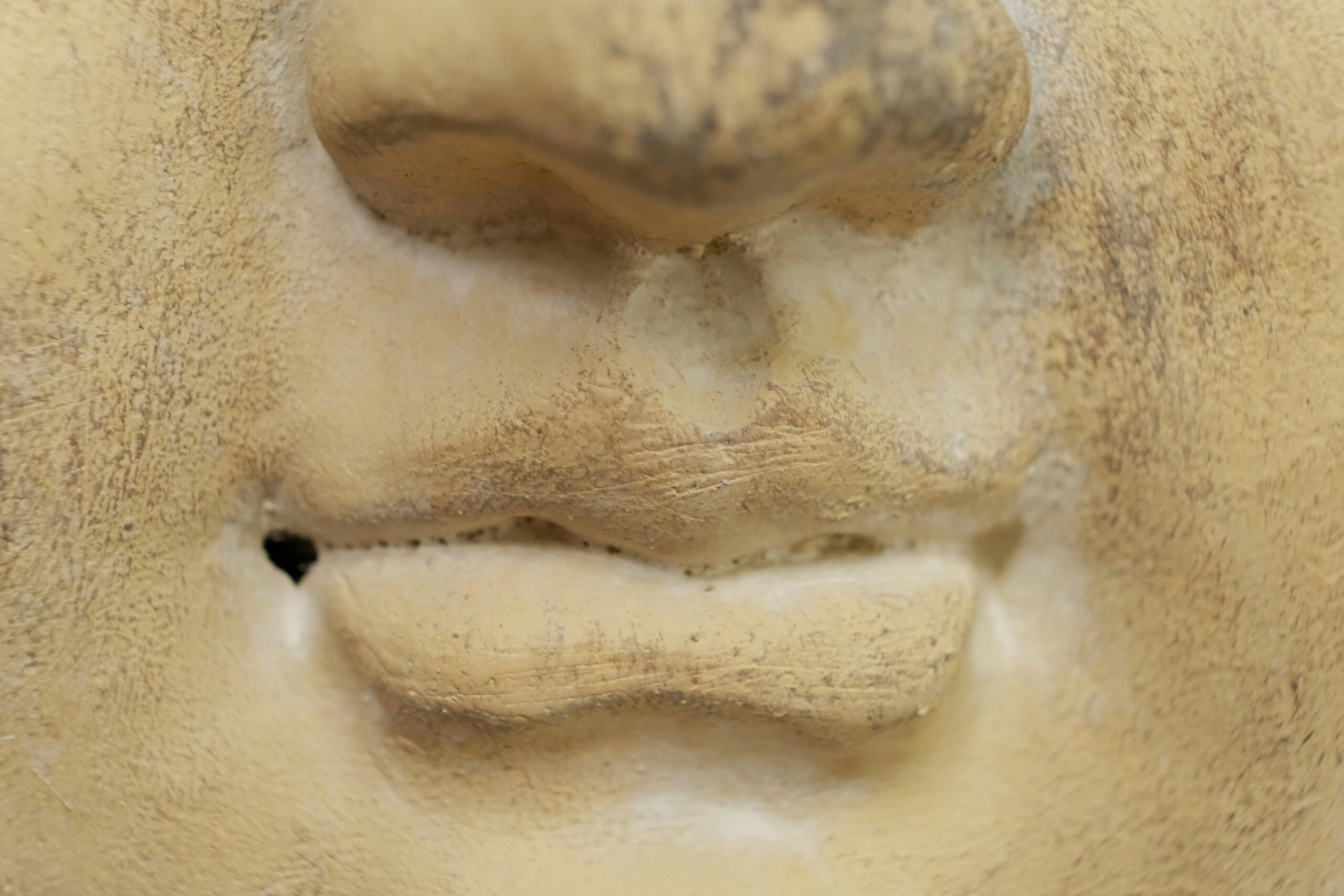

Clinically, syringomas present as small, firm, rounded papules that range from one to three millimeters in diameter. Their color varies, appearing skin-toned, yellowish, white, or hyperpigmented. Some may appear translucent or cystic. These papules are often symmetrically distributed, most frequently on the lower eyelids and cheeks. Eruptive syringomas, a more extensive presentation, may spread across the trunk, chest, abdomen, upper extremities, and even the genital region. While syringomas are usually asymptomatic, some individuals may experience mild itching, particularly when sweating or if the lesions are located in sensitive areas such as the vulva.

The appearance of syringomas can vary depending on an individual’s skin tone. In those with darker skin types, these papules may appear as yellowish, hypopigmented, or hyperpigmented lesions. Despite their benign nature, syringomas can be of cosmetic concern, particularly when they appear on the face. In rare cases, syringomas associated with Down syndrome may calcify, leading to a condition known as calcinosis cutis, in which calcium deposits form within the lesions.

Diagnosing syringomas is typically straightforward due to their characteristic clinical presentation. However, when confirmation is needed, a skin biopsy may be performed. Histological examination reveals normal epidermis overlying multiple small ducts and epithelial cords embedded within the dermis. These ducts are lined by two rows of flattened epithelial cells, with an outer layer that bulges outward, creating a distinctive comma-like tail, often described as resembling a tadpole. The surrounding stroma is sclerotic, further distinguishing syringomas from other dermatological conditions. Clear cell syringomas, which contain glycogen-rich epithelial cells, may indicate the need for further evaluation of glucose metabolism, given their association with diabetes. In cases where deeper involvement is suspected, a full-thickness biopsy may be necessary to differentiate syringomas from more aggressive conditions such as microcystic adnexal carcinoma, which infiltrates deeper layers of the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

A number of skin conditions can mimic syringomas, making differential diagnosis important. These include xanthelasma, trichoepitheliomas, milia, Fox-Fordyce disease, microcystic adnexal carcinoma, and basal cell carcinoma. While syringomas are entirely benign, their resemblance to certain malignancies warrants careful evaluation in some cases.

Since syringomas are harmless, treatment is not medically necessary. However, for individuals who seek cosmetic improvement, several options are available, though results are often inconsistent, and recurrence is common. Topical treatments such as long-term tretinoin therapy can help improve the appearance of syringomas, and in cases where itching is a concern, topical atropine sulfate may provide relief. More invasive procedures, including carbon dioxide (CO2) and erbium YAG laser therapy, electrosurgery, and surgical excision, can be employed to remove the lesions. However, these interventions must be approached with caution, as syringomas extend deep into the dermis, increasing the risk of incomplete removal and recurrence. Additionally, individuals with darker skin tones may be more prone to complications such as hypertrophic or atrophic scarring and post-inflammatory pigment changes.

Spontaneous resolution of syringomas is exceedingly rare. Even with treatment, they have a tendency to recur, particularly after superficial removal methods. While they do not pose any health risks, their persistence and cosmetic impact can be frustrating for some patients. Those considering treatment should discuss potential outcomes and risks with a dermatologist to determine the most appropriate approach based on their individual skin type and aesthetic concerns.

Ultimately, syringomas are a benign yet often bothersome skin condition that primarily affects the face, particularly the eyelids. Though they are generally asymptomatic, their cosmetic impact may prompt individuals to seek treatment. While several therapeutic options exist, none guarantee permanent resolution, and recurrence remains a challenge. With careful evaluation and a tailored treatment approach, patients can manage syringomas effectively while minimizing the risk of complications.