Hyperhidrosis is a condition characterized by excessive and uncontrollable sweating, caused by the eccrine sweat glands, which produce a weak salt solution. These glands are distributed throughout the body but are densely packed on the palms and soles, with about 700 glands per square centimeter.

Primary hyperhidrosis affects 1–3% of the US population and typically begins during childhood or adolescence. It may be hereditary and is notably prevalent among Japanese individuals. In contrast, secondary hyperhidrosis is less common and can occur at any age. Primary hyperhidrosis is often linked to overactivity of the hypothalamic thermoregulatory center in the brain, which communicates with the eccrine sweat glands through the sympathetic nervous system. Various triggers can induce sweating episodes, including hot weather, exercise, fever, anxiety, and spicy food. Secondary hyperhidrosis has localized causes such as auriculotemporal syndrome (gustatory hyperhidrosis), stroke, spinal or peripheral nerve damage, surgical sympathectomy, neuropathy, brain tumors, and chronic anxiety disorder. Generalized causes include obesity, diabetes, menopause, an overactive thyroid, cardiovascular disorders, respiratory failure, other endocrine tumors like phaeochromocytoma, Parkinson’s disease, Hodgkin lymphoma, and certain medications such as alcohol, caffeine, corticosteroids, and antidepressants.

Hyperhidrosis can manifest as either localized or generalized. Localized hyperhidrosis typically affects the armpits, palms, soles, face, or other specific areas, whereas generalized hyperhidrosis impacts most or all of the body. The condition can also be categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary hyperhidrosis generally starts in youth and might persist throughout life, often involving the armpits, palms, and soles symmetrically, and usually decreases at night and stops during sleep. Secondary hyperhidrosis, being rarer, might present unilaterally and asymmetrically or as a generalized condition, and it can occur at night or during sleep, often due to underlying endocrine or neurological issues or medication effects.

The impacts of excessive sweating are significant. Axillary hyperhidrosis leads to damp, stained clothing that must be changed multiple times a day, and wet skin folds are susceptible to chafing, irritant dermatitis, and infections. Palmar hyperhidrosis causes slippery hands, which can lead to social discomfort like avoiding handshakes, leaving marks on paper and fabrics, difficulties with neat writing, and electronic equipment malfunctions. Plantar hyperhidrosis affects the soles, causing an unpleasant odor, ruined footwear, and making the feet prone to blistering dermatitis and infections like tinea pedis and pitted keratolysis.

Hyperhidrosis is typically diagnosed through clinical evaluation. Tests to determine the underlying cause are generally unnecessary for primary hyperhidrosis but may be required to diagnose secondary hyperhidrosis. The Minor test is commonly used to identify the specific sites of localized hyperhidrosis. This involves painting the skin with an iodine solution, which is then allowed to air-dry before starch is applied. Areas of sweating will change the iodine-starch combination to a dark blue or black color. For secondary generalized hyperhidrosis, screening tests based on other clinical features might include assessments of blood sugar levels, glycosylated hemoglobin, and thyroid function.

The management of hyperhidrosis includes general measures such as wearing loose-fitting, stain-resistant clothes, changing damp clothing and footwear promptly, using socks infused with silver or copper to reduce odors and infections, and employing absorbent insoles. Non-soap cleansers and cornstarch powder after bathing can help, as can avoiding caffeinated products and discontinuing any medications that may be contributing to the condition. The application of antiperspirants is a key treatment strategy.

Topical antiperspirants, which include products ranging from creams to aerosols and gels, typically contain 10–25% aluminum salts to mitigate sweating. Clinical-strength products using aluminum zirconium salts are particularly effective. Topical anticholinergics like glycopyrrolate and oxybutynin gel have also been successful in reducing perspiration. These antiperspirants should be applied to dry skin after showering and washed off in the morning if they cause irritation, with application frequency adjusted as needed.

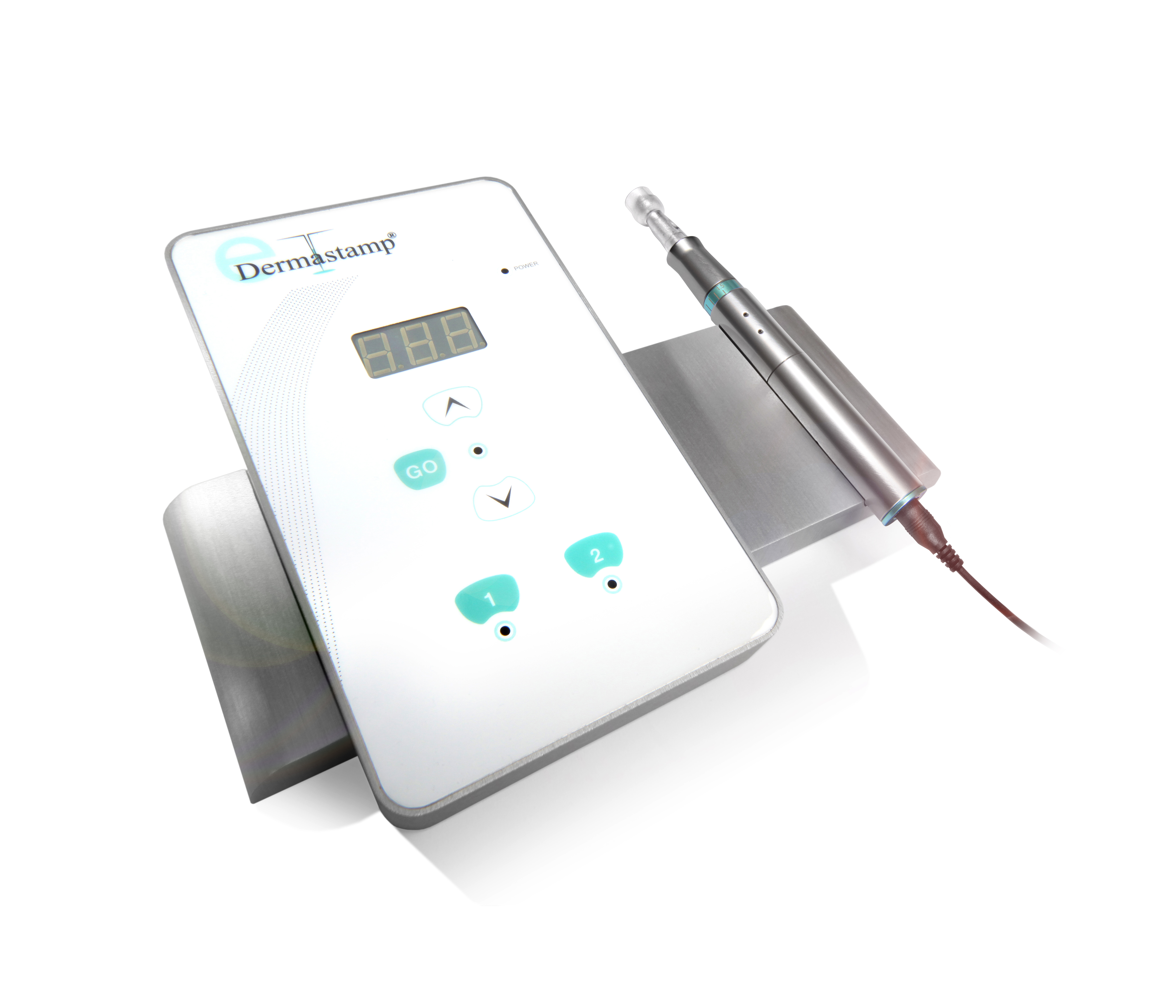

Iontophoresis is another treatment option, involving the use of electric currents in water or glycopyrronium solution to treat the palms, soles, and armpits. This method requires daily sessions initially, then less frequently over time, though it may cause discomfort or dermatitis and is not always effective.

Oral medications include anticholinergics such as propantheline and oxybutynin, which may cause side effects like dry mouth and blurred vision and should be used cautiously, especially in the elderly due to the increased risk of dementia. Beta-blockers, which mitigate the physical effects of anxiety, and other medications like calcium channel blockers and alpha-adrenergic agonists, may also be beneficial for some patients.

Botulinum toxin injections are approved for treating hyperhidrosis of the armpits and are being investigated for use in other areas. Surgical options include removal of sweat glands through various methods like tumescent liposuction, subcutaneous curettage, and advanced techniques like microwave thermolysis. Sympathectomy, a more invasive procedure, may be considered for severe cases but carries risks such as compensatory sweating and serious complications like Horner syndrome.

The prognosis for localized primary hyperhidrosis often improves with age, whereas the outlook for secondary hyperhidrosis depends on its underlying causes. Ongoing research aims to develop safer and more effective treatments, including new topical and systemic therapies.